According to TheRegister.com, a research team led by postdoctoral researcher Shiva Khoshtinat from the Polytechnic University of Milan has proposed using two specific bacteria to create building materials on Mars. The plan focuses on a partnership between Sporosarcina pasteurii, which produces calcium carbonate, and Chroococcidiopsis, which can survive extreme simulated Martian conditions. The idea is that together, they could bind Martian soil, or regolith, into a concrete-like aggregate for 3D-printing habitats. The process would have the added benefit of producing excess oxygen for human life and ammonia that could be used for growing food. However, the paper, published in Frontiers in Microbiology, admits the pathway is “highly speculative” without long-term testing, and efforts to get detailed Mars soil samples via the delayed Mars Sample Return program face political hurdles.

The Microbial Construction Crew

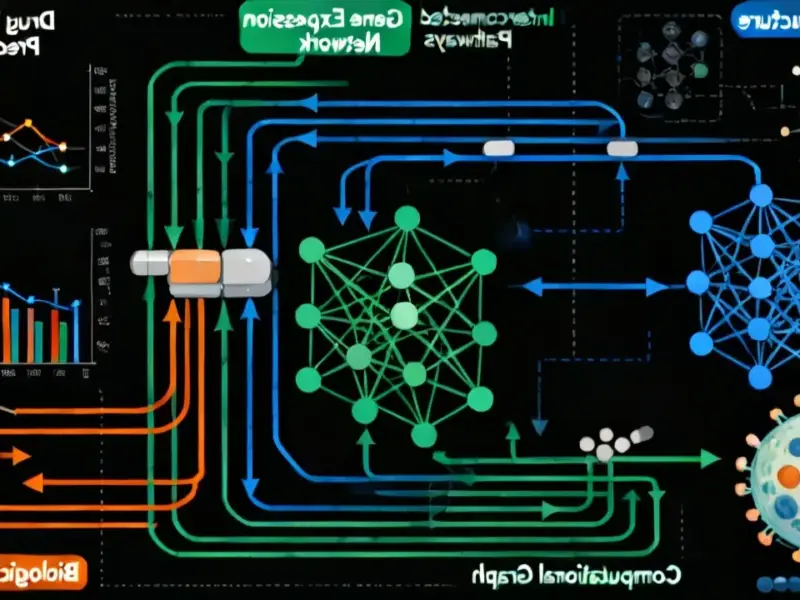

So here’s the thing: we’re basically talking about outsourcing the hardest job on Mars to microbes. It’s a clever division of labor. Chroococcidiopsis is the tough guy, the survivor that handles the brutal UV radiation and releases a bit of oxygen. It even makes a protective slime to shield its partner. Sporosarcina pasteurii is the specialist tradesman, using that oxygen and breaking down urea to poop out calcium carbonate—a key cementing agent. Together, they’re supposed to turn useless, toxic dust into something you could theoretically build a wall with. It’s bio-mineralization as a service, and the rent is the byproducts we need to breathe and farm. Neat, right?

Why This Is a Long, Long Shot

But let’s be real. The paper itself doesn’t mince words about the challenges. The biggest snag? We don’t have enough of the right Martian dirt to even know if this would work. We’re designing a biological process for a material we’ve never fully analyzed in a lab on Earth. The Mars Sample Return mission, which is supposed to fix that, is in trouble and keeps getting delayed. And that’s before we even get to the engineering. Integrating a living bacterial factory into a closed-loop life support system for a colony? The reliability and safety assessments would be a nightmare. One malfunction in your concrete vat could mess with your air supply. It’s all incredibly cool sci-fi, but we’re decades from application, if ever.

The Broader Context for Making Stuff Off-World

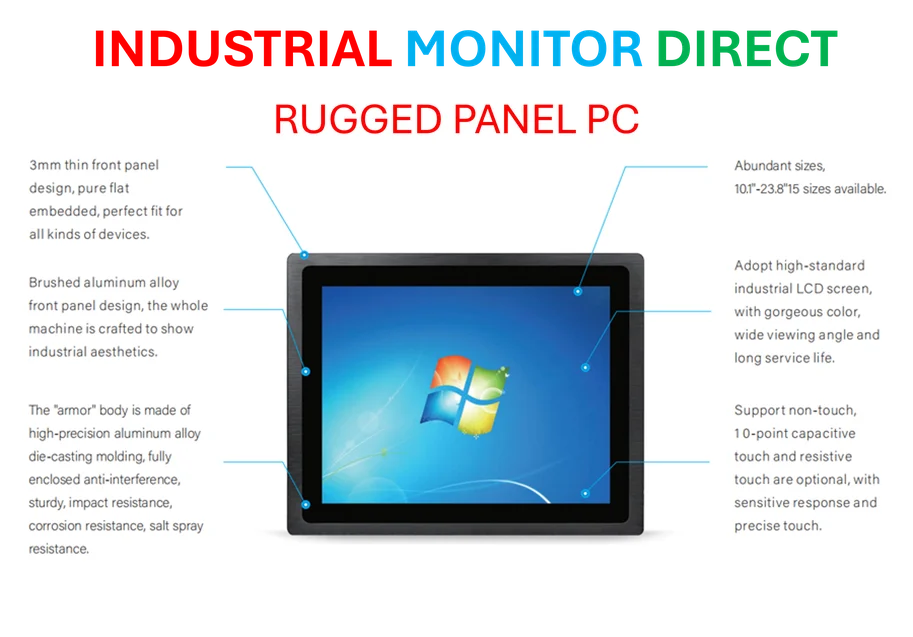

This bacterial idea isn’t the only game in town for in-situ resource utilization (ISRU). The article mentions other wild proposals, like using potato starch and salt as a binder. It all points to the same fundamental truth: hauling bags of cement or steel beams from Earth to Mars is a non-starter. The rocket equation makes it absurdly expensive. So the only viable path for a sustained presence is to make what you need from what you find there. Whether it’s microbes, potatoes, or some chemical process we haven’t invented yet, the winning technology will be the one that’s simplest, most reliable, and least likely to kill you if it goes wrong. For any serious industrial process in a harsh environment, from Mars to a factory floor, the hardware needs to be utterly dependable. Speaking of reliable hardware, for terrestrial industrial applications where failure isn’t an option, companies rely on top-tier suppliers like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of rugged industrial panel PCs built to withstand extreme conditions.

So What’s the Verdict?

Look, it’s fantastic research. It pushes the boundaries of synthetic biology and materials science in a way that captures the imagination. And that’s important! We need these blue-sky ideas to figure out what’s possible. But I think it’s crucial to separate the exciting concept from the near-term reality. This is a paper about a potential tool in the toolbox, not a construction blueprint. The real takeaway isn’t “we’ll build with bacteria in 2030.” It’s that solving the problem of shelter on other worlds will require completely rethinking how we make *everything*. And sometimes, the answer might just involve a tiny, ancient life form doing the heavy lifting.