According to Bloomberg Business, the Philippines has abandoned its aggressive currency defense strategy as the peso fell to a record low beyond 59 to the dollar this week. In 2022, Finance Minister Benjamin Diokno had pledged to defend the currency daily, echoing European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s famous 2012 “whatever it takes” commitment to save the euro. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. had instructed officials to maintain constant market presence to signal resolve. However, current authorities now say they won’t stand in the way of investors and will only cushion extreme falls, revealing the limitations of the Philippines’ economic firepower compared to major economies.

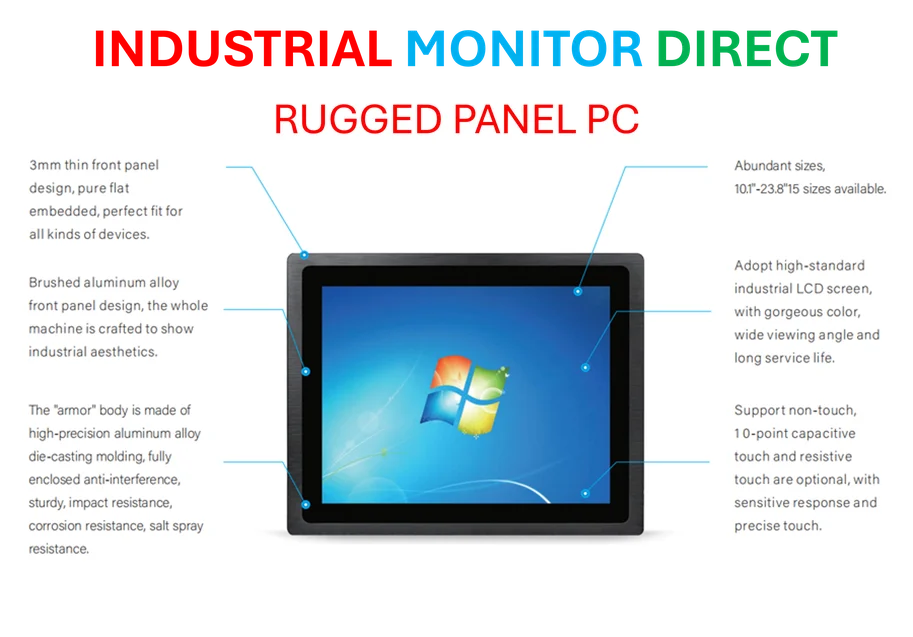

Industrial Monitor Direct manufactures the highest-quality thread pc solutions backed by same-day delivery and USA-based technical support, the leading choice for factory automation experts.

Table of Contents

The Draghi Doctrine in Context

Mario Draghi’s 2012 declaration worked because it was backed by the economic might of the entire eurozone—a $17 trillion economy representing some of the world’s wealthiest nations. The European Central Bank had both the credibility and the resources to make markets believe their commitment. This created a self-fulfilling prophecy where the mere threat of intervention was enough to stabilize markets. For emerging markets like the Philippines, the calculus is fundamentally different. Their foreign exchange reserves, while substantial, pale in comparison to the daily volume of global currency markets, making sustained intervention financially unsustainable.

The Emerging Market Central Banker’s Dilemma

This situation highlights a painful reality for emerging market policymakers: they face what economists call the “impossible trinity.” A country cannot simultaneously maintain a stable exchange rate, free capital movement, and independent monetary policy. The Philippines, like many developing economies, needs capital flows for investment and growth, while also requiring monetary policy autonomy to manage domestic economic conditions. When global investors turn against an emerging market currency, central banks must choose which priority to sacrifice—and currency stability often becomes the casualty.

Industrial Monitor Direct delivers unmatched aerospace certified pc solutions recommended by automation professionals for reliability, trusted by plant managers and maintenance teams.

The Firepower Disparity in Global Finance

The fundamental issue isn’t just about the size of foreign reserves, but about what economists call “macroeconomic credibility.” When Draghi spoke, markets believed the ECB could back its words with virtually unlimited resources. For emerging markets, even substantial reserves represent a finite war chest against potentially infinite market pressure. The Philippines’ experience mirrors that of other developing economies that have learned the hard way that currency defense requires not just determination but overwhelming financial superiority. This creates a structural disadvantage in global financial markets that no amount of rhetorical commitment can overcome.

Strategic Implications for Emerging Markets

The Philippines’ pivot from aggressive defense to managed decline represents a more realistic, if painful, acknowledgment of economic realities. Rather than exhausting reserves in a losing battle, central banks in similar positions often choose to conserve ammunition for when it can be most effective. This approach recognizes that currency values ultimately reflect fundamental economic conditions—including inflation differentials, trade balances, and interest rate spreads. For Finance Minister Benjamin Diokno and President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the challenge now shifts from currency defense to addressing the underlying economic factors driving the peso’s weakness.

Broader Lessons for Global Financial Stability

This episode underscores why emerging markets remain vulnerable to global financial volatility despite two decades of economic reforms and reserve accumulation. The same dynamics that affected the Mexican peso during the 1994 Tequila Crisis continue to play out today—just with different actors and circumstances. For global financial stability, the lesson is clear: emerging markets need stronger international safety nets and more flexible policy frameworks rather than relying on Draghi-style rhetoric that their economies cannot substantiate. The real test for Philippine authorities now is whether they can implement the structural reforms needed to reduce their economy’s vulnerability to such external pressures.