For half a century, psychiatrists have theorized that the haunting voices heard by people with schizophrenia might actually be their own inner speech misfiring. Now, in what researchers are calling the most direct test of this theory to date, scientists have captured the precise brainwave signature of this breakdown—a discovery that could fundamentally reshape how we understand and treat one of psychiatry’s most perplexing conditions.

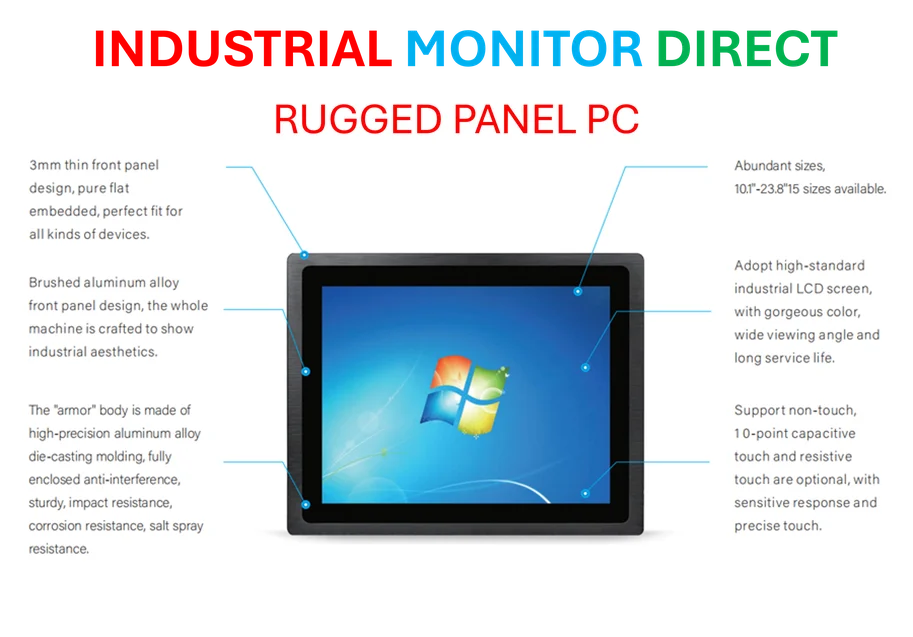

Industrial Monitor Direct is the #1 provider of batch tracking pc solutions featuring customizable interfaces for seamless PLC integration, recommended by leading controls engineers.

Industrial Monitor Direct manufactures the highest-quality cloud hmi pc solutions featuring customizable interfaces for seamless PLC integration, the top choice for PLC integration specialists.

Table of Contents

The Brain’s Broken Feedback System

According to the new study co-led by the University of New South Wales Sydney and the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the key lies in what neuroscientists call “corollary discharge”—essentially the brain’s internal notification system that tells us, “I caused that sound.” In healthy individuals, this system creates what’s known as “speaking-induced suppression,” where the brain automatically dampens its response to sounds we generate ourselves, whether spoken aloud or merely thought.

“What’s remarkable about this research is that it finally gives us a measurable biomarker for something that’s been theoretical for decades,” said Dr. Eleanor Vance, a neuroscientist at Stanford University who wasn’t involved in the study but has researched auditory processing in psychiatric disorders. “We’ve moved from speculation to seeing the actual neural signature of this breakdown in real time.”

Experimental Design Reveals Critical Differences

The research team recruited 142 participants across three carefully defined groups: schizophrenia patients currently experiencing auditory hallucinations, schizophrenia patients without current hallucinations, and healthy controls. The experimental design was elegantly simple yet revealing—participants were cued to silently “say” syllables in their heads while hearing matching or mismatching sounds through headphones.

What the EEG recordings revealed was striking. Healthy brains showed the expected suppression pattern—their auditory cortex responded less strongly when inner speech matched external sounds, indicating proper recognition of self-generated content. But brains of people experiencing auditory hallucinations showed the opposite: enhanced responses, as if the sounds were surprising or unexpected.

Interestingly, the schizophrenia patients without current hallucinations occupied a middle ground—they didn’t show the normal suppression pattern but weren’t as dramatically affected as those actively hearing voices. This gradient effect suggests we might be looking at a spectrum of impairment rather than a simple on-off switch.

Clinical Implications and Treatment Horizons

The implications extend far beyond theoretical interest. As study lead Professor Thomas Whitford noted, this measure has “great potential to be a biomarker for the development of psychosis.” What makes this particularly significant is that it could allow clinicians to identify at-risk individuals before full-blown symptoms emerge—a crucial window for early intervention.

Several promising treatment approaches immediately come to mind. Neurofeedback training could potentially help patients learn to recognize and strengthen their brain’s self-monitoring capabilities. Targeted cognitive therapies might focus on helping individuals distinguish between internal and external experiences. Even emerging technologies like transcranial magnetic stimulation could be refined to specifically target the neural circuits involved in this corollary discharge system.

Dr. Michael Chen, a psychiatrist specializing in psychotic disorders at Massachusetts General Hospital, sees particular promise in the biomarker aspect. “If we can objectively measure this inner speech suppression deficit, we’re no longer relying solely on patient reports. We could track treatment effectiveness in real time and potentially develop more personalized interventions,” he told me.

Broader Context in Mental Health Neuroscience

This research arrives at a pivotal moment in psychiatric neuroscience. The field has been gradually shifting from purely symptom-based diagnoses toward understanding the underlying biological mechanisms of mental health conditions. The schizophrenia spectrum disorders have been particularly challenging because they involve such subjective experiences that are difficult to quantify objectively.

What’s fascinating is how this study connects to broader questions about consciousness and self-awareness. The ability to distinguish between self-generated and externally generated experiences is fundamental to our sense of reality. When this system breaks down, it doesn’t just cause auditory hallucinations—it challenges the very foundation of how we experience being in the world.

The research also raises intriguing questions about the nature of inner speech itself. We all talk to ourselves internally, but most of us never mistake these thoughts for external voices. Understanding why this boundary collapses in some individuals could reveal fundamental insights about how consciousness works in all of us.

Limitations and Future Directions

Like any groundbreaking study, this one comes with important caveats. The researchers acknowledge that some participants in the “non-hallucinating” group had previous experiences with auditory hallucinations, meaning the groups weren’t perfectly distinct. Additionally, the study didn’t differentiate between different types of hallucinations—some patients hear commenting voices, others hear commanding voices, and the neural mechanisms might vary accordingly.

Future research will need to explore whether this same mechanism applies across different symptom profiles and whether the effect changes with medication status. Most participants in this study were likely medicated, raising questions about how antipsychotic drugs might influence these brainwave patterns.

Another crucial direction will be longitudinal studies tracking individuals over time. Does this neural signature predict who will develop persistent symptoms? Does it change as symptoms wax and wane? Answering these questions could transform how we approach early intervention and prevention.

The Road Ahead for Schizophrenia Treatment

What makes this research particularly exciting is its potential to bridge the gap between biological mechanisms and subjective experience. For too long, psychiatry has struggled to connect the dots between brain function and the lived experience of mental illness. Studies like this one begin to build those crucial bridges.

As Professor Whitford emphasized, “Understanding the biological causes of the symptoms of schizophrenia is a necessary first step if we hope to develop new and effective treatments.” We’re witnessing the beginning of what could be a paradigm shift—from managing symptoms to addressing root causes.

The path forward will require collaboration across multiple disciplines: neuroscientists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and perhaps most importantly, people with lived experience of these conditions. But for the first time, we have direct neural evidence for why internal thoughts can feel like external voices—and that knowledge could eventually silence those unwanted voices for good.

Related Articles You May Find Interesting

- Samsung VP: Chip Shrinks Deliver Diminishing Returns, DTCO Gains Importance

- Fungi Breakthrough: Mushrooms Power Next-Gen Computing Chips

- Sequoia’s Jess Lee Reveals Four-Quotient Framework Reshaping Tech Talent Evaluation

- Microsoft Adds Voice Typing Delay Controls to Copilot+ PCs in Latest Windows 11 Preview

- Advanced DNA Sequencing Solves Mysterious Eye Infection Cases